On Digital Art

GLITCH, ALGORITHMS AND EARLY COMPUTER ART

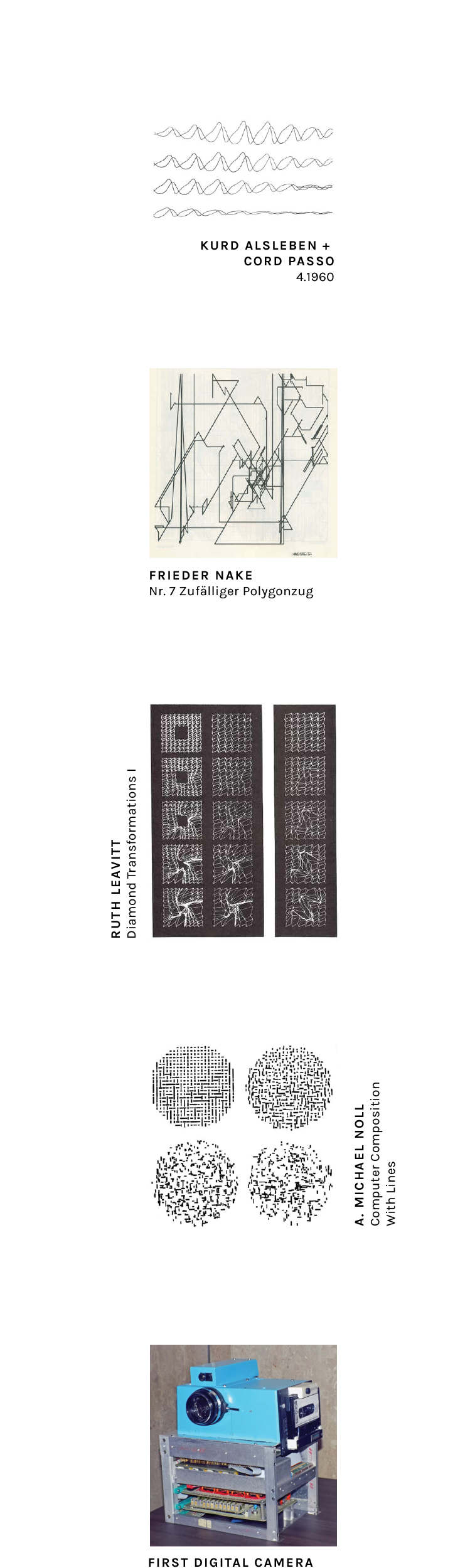

The first ‘computer art’ was created in the early 1960s, not by traditional artists but by the people working directly with the computers – people who were more in tune with numbers and computer science that fine art and drawing. Initially, the goals of these ‘artists’ were simply to explore their tools and push at the boundaries of just what could be created.

The first images were created with the help of random number generation and plotter printers – leaving a large amount of the ‘drawing’ to a machine. The output created by these machines opened up a new field of manufacturing and robotics in the art world – a person with little artistic merit could input a selection of values and instructions into the computer and create an aesthetically pleasing artwork at the end of it – leaving the artist to take the role of curator rather than creator.

Early pioneers approached the genre from a mathematical aspect – creating a set of instructions intended to test the limits of the machine, to discover what could be created and how.

After seeing what could be created, new users began to emerge from art and design backgrounds. With the help of improved user interfaces, or by means of a collaboration with programmers and the computer literate, the world of digital computer art started to open up to those with a greater interest in aesthetics and artistic concept.

Ruth Leavitt, was one of these pioneers – with an interest in the prospects of computing piqued by her Computer-Science-lecturing husband.

Here she discusses her excitement at the future possibilities of developing art within a computer environment:

I find that using the computer I do not have to give up my traditional role as artist. The machine acts as a multifaceted tool which I control. When I began to use the computer I had no knowledge of programming…It is the option to create one’s own work tools which, in my mind, makes computer art unique. A new role is now open to the artist in addition to the traditional one of making objects. He can create programs for himself, other artists, and perhaps even for the public.

Leavitt, 1976

This last comment shows a great level of insight into how the influence of the computer has developed and spread, and highlights how early on the use of collaboration and sharing became a necessity for improvement and learning. She goes on to expand on this by citing how widely accessible computers will be to artists of the future, and how the intrinsic nature of coding and programming will form the basis for much of this accessibility,

“It will be ‘the public art’ because the public will be generating works of art with programs that artists have created.”

Leavitt, 1976

During the transition from analogue to digital, work was often produced using traditional media, albeit often with modified or automated processes. One main example of this is the use of the pen plotter to transfer an instruction from the code or program relayed to the computer, to a direction for a mechanised pen to travel, thus performing like an early form of printer.

Similarly, early digital photography involved the use of an analogue tape to capture the data during the 23 second exposure time, which could then be viewed instantly by the photography on a standard television – with no need for film processing.

With this ‘hybridised’ technology, a lot of potential for error and flaw remained – as well as the artist’s input being in part translated and dictated by the computer algorithm, the processes used to publish the work would also result in minor differences and unexpected alterations. Often these flaws can lend a comforting human-like element to the clinical, robotic nature of the computer image.

Eventually, evolution removed the need for most analogue components and gave us the incredibly advanced computers we use today. With the untold opportunities for creation we have at our disposal, it is interesting to see designers and makers now using digital techniques to incorporate craft and vintage elements into their work, combating the sterility of our ever-closer-to-perfect digital capabilities.

One area where this is particularly prevalent is photography, with the current resurge in popularity for instant, Lomography and ‘toy’ film cameras, and the countless Instagram (and other) filters made to replicate an analogue error or aging effect onto their otherwise crisp image.

This ‘intentional digital error’ is a technique popular in much of the online photo sharing community – although with the same set effects available to every user there is little scope for variation. Whilst it encourages creativity and photography, it also discourages experimentation and limits artistic variation by providing a cookie-cutter overlay for the artist to hide behind. If the filter obscures any imperfections in the original image, it is ready to be shared in the never-ending feed of ‘aesthetic’ images that fit the zeitgeist without needing compositional or artistic skill.

Analogue photography retains much of its original element of suspense – in fact as a result of the trend photographers are modifying their cameras and processing techniques in order to find new and exciting ways to create a ‘wrong’ or surprising output.

This intentional modifying of images translates back into the digital world on another level – with the emergence of glitch art, where the artist intentionally hacks away to get at the data or bare bones of an image, and cause it to corrupt, break or malfunction in such a way that a new version of the image is created. This can be done in such a way to resemble the act of processing film – what the artist intends to alter, and the level of decay or error introduced, can be controlled to a point, but ultimately this is decided by the process – errors provide the aesthetic interest.

Another facet to this theme is the unintentional digital errors that still prevail, through faulty tools, accidental corruption, or transference and conversion errors. A great source for these errors are the less aesthetically led, large scale photography and video projects created solely for online use – namely mapping technology, and webcam imagery. As there is less of an onus on the composition and attractiveness of these images, and more of a want to collect and share data and information, the image is uncontrived in a way that allows the user to stumble upon beautiful scenes, candid moments and generally terrible photography in a voyeuristic way. There is often beauty and interest in the errors and oddities picked up by these gaze-less cameras.

The New Aesthetic movement, headed up by blogger and digital experimenter James Bridle, examines the intertwining of this digital prevalence in our everyday lives. One of his ideals is the need to look forward, and shake off the nostalgic vibe that is often present in our culture- to embrace the technological revolution and its integration with our environment in a way that blurs the boundaries between the virtual and the real for the benefits of society and culture.

VALUE, OWNERSHIP AND SHARING

With the ability to write a code or set of instructions and set a computer to ‘go,’ allowing it to design infinite variations of work, the question of the art’s value is brought into play. As the computer has the power to work with and create infinite combinations, the work that the early artists produced is merely a sample of the outcomes that the algorithms and programs they wrote could have produced, meaning their choice of what to send to the plotter, and what to publicise, would have been the biggest decision that they could make in terms of aesthetics.

This brings in the question of the art’s value – with this increased availability to have a unique original piece art at a low cost and quick production, the art produced wouldn’t take days to produce, and any hand-produced ‘copy’ or ‘forgery’ is likely to take more effort and time than the original piece.

In 1966 Noll highlighted the ability computer-created imagery has to reproduce and artists techniques by creating a computer program to draw a reproduction of Mondrian’s 1917 Composition with Lines – by allowing a code to run with stylistic elements of another’s work (particularly the bold abstracts of Mondrian), it is almost certain that one of the infinite iterations will resemble a composition closely related to the artist’s. This ‘copy’ was used as a test of the public’s perception – very few could identify the computer-generated image in a side by side comparison, and when asked to select a preference over half chose the ‘copy.’

With the emergence of the internet, the opportunities to copy and share work grew vastly – now a person can ‘own’ a piece of art at the click of the button and zero cost. The limit on the number of copies became infinite – as the work can be downloaded and saved ad infinitum, there is no sense of having the ‘original’ copy – nothing is susceptible to damage or loss as it will exist somewhere else, and any copy of the image can be changed and modified and saved as a new image at every stage of the way – allowing the piece to become the best possible version of itself, because there is no danger of spoiling it.

The use of historical matter as a basis for digital alterations or collages is prevalent as generally the artist wants the viewer to recognise the piece – by using older media as a basis, the less saturated art environment means that more people will share the same iconic and instantly recognisable images. With the development of the internet and its use as a marketing and sharing tool for artists and designers, the amount of art available for us to access is forever expanding, which will generally provide short ‘bursts’ of popularity for individual images or collections, as opposed to more historical art, with its longer bouts of fame and recognition for artist which provides a common ground- point for viewers to relate to.

The use of older media in online art reflects the culture of improving as a collaborative force – from forum based Photoshop contests and memes, to collages in an online artist’s portfolio, the inevitable multiple uses of one source image provide a selection from which ideas can spring from – with comparatively similar images it is easier to subjectively choose which is superior, and therefore this collective refinement of taste and growing standard of skill to attain creates an atmosphere of improvement.

The use of recognisable elements in collage can also bring an element of politics to art – the ease to create and share a provocative image digitally means art and politics converge to create more conceptually driven creatives, reminiscent of the subverted collages of the Situationalist movement.

By sharing and downloading others work, aspiring digital artists can also utilise the work by modifying and editing it with their own additions – the culture of art as a remix-able element is one that is emerging with the popularity of blogging and sharing platforms such as Tumblr, Pinterest, Instagram and Twitter, where people can talk and share with others with the same interest, and the value of a work is placed as much on its popularity as its aesthetics.

Multimedia artist Mark Amerika creates work inspired by glitch, data and digital culture in a variety of media. In a talk of his which I attended he cited a quote which he felt was a relevant inspiration to much of his work, and the experimental nature of working with new digital media

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Samuel Beckett

The quote applies to many aspects of life, but in the context of digital art is specifically relevant to glitch art – pushing the boundaries of a ‘new’ medium and taking the failures as positive outcomes, seeing the beauty in the error.

Amerika calls much of his work ‘applied mixology’ – having started out as an experimental writer, his work crosses media boundaries and becomes a complex ‘mish-mash’ of influences and outputs, expressing his ideas and thoughts without boundaries. From creative writing, he moved on to VJ-ing – mixing video clips together in a live environment, combining audio, visual and live performance art.

He cites one of his first experiences of social media ‘sharing’ as a non-digital transaction between a peer, having been given a VHS of Guy Deboard’s Society of the Spectacle – itself already a mix of found film clips and philosophical theory. As part of the DJ Rabbi group the tape was digitised and further remixed using imagery found through google image searches.

Situationalist principles are an influence on his work – a mid-century founded group who explored the crossovers between art and life, seizing the opportunity to create constructed situations and events intended to improve or challenge the participant’s perception of their environment, as a diversion from the banal repetitiveness of life. The group felt the general population and culture was being imposed upon and engulfed by the media – with the media influencing the consumer as opposed to the consumer influencing the media. Digital art itself is a way for the consumer to feel in control – anything can be shared, published and viewed – with the wealth of choice available online there is less scope for ‘brainwashing’ or propaganda fears – however the internet can also be censored and controlled to give consumers a restricted number of options whilst retaining the ‘spectacle’ of offering choice. Remix culture was also an idea favoured by the Situationalists, taking political and other imagery and reworking it to create a piece with a completely unrelated or opposite meaning.

Amerika spoke about his ‘immobilité’ project from early 2007- he aspired to create a full-length feature film created entirely from mobile footage.

A lot of Amerika’s moving image work makes a feature of subtitles – and their (ir)relevance to the scene and the viewers perception of it.

A large influence in the creation of the film was ‘foreign’ or art-house films – where the viewer has to concentrate fully in order to extract meaning and narrative and even then will struggle to process every layer.

In the production of the immobilité film, the small production team pooled their influences, creating a remixed influx of ideas and readings- on influence, experimental filmmaker, Stan Brakhage, coined the term “moving visual thinking,” which is relevant to much of Amerika’s work.

He wanted to mix the amateur elements of this Youtube-style accessible level of filming, with the more avant-garde, less accessible skill of digital glitch manipulation of the imagery. The data was captured on lo-fi devices, and post-production editing done on a computer, manipulating the footage to create almost gif-like repetitions in parts, reminiscent of vintage stereoscopic images.

The work was exhibited as part of The Streaming Museum, a project which shows new media films on worldwide screens and online, giving different viewer experiences – by showcasing the work on an urban screen, an un-filtered audience, without necessarily having a prior interest or intention to view the work, is subjected to the film as an enhancement to their environment – reminiscent of the Situationalist principles. This project allows the work to come ‘full-circle’ – having been created by the artist, Amerika, then exhibited on a screen to a diverse audience, the location of the screen viewed on a webcam and this online stream in turn captured and shared by the artist – a remix of the context of his own work. This challenges the idea of public space as a real location, and public space as a virtual place on the internet.

A lot of Amerika’s work explores the multi-layered, experiential aspects of digital media – how a piece of work can be shared and adapted, and viewed in an array of surroundings – giving the viewer complete to zero control over the experience. The work plays on the infinite aspects of the digital space – there is no limit to the audience in terms of size, location, education etc, and the work is able to live forever in a number of states – there is no need to claim a piece of work is finished before exhibiting it – the work can continue to grow or be recycled without losing the previous incarnations, because of the ability to create unlimited copies.

By using this accessible medium, Amerika wants to challenge the perception of success and the hierarchy of the arts culture. The influx of technology makes creativity accessible to everyone, and the creation of sharing and peer-supported platforms such as Kickstarter make large-scale projects an attainable goal for even the smallest artist. The ability to use the internet as a means of communicating and sharing work as a group takes away the traditional confines of ‘studio’ working – a collaboration can happen between artists 5,000 miles away as easy as between artists 5 minutes away when digital media is involved.

This disconnection can cause the persona of an artist to become blurred – when a group has created something, or when an artist has used such a vast amount of re-purposed material, how much of the artist is reflected in the work?

Work can be reworked reproduced shared and changed again ad infinitum – everything is a freely accessible collaboration – does the work gain or lose value because of this?

In this vein, an image can be built up and altered countless times by a variety of contributors before it reaches a point where it gains popularity – thus becoming a multi-authored collaboration. Sites such as DeviantArt and Tumblr are awash with users creating content purely for the purposes of sharing it with others – from textures to apply to images, website designs and fonts to entire programs and operating systems, the trend for Open Source material is ever growing. With multiple authors, and a world full of influences with the opportunity to add something to the piece, it can constantly be improved – with each contributors addition potentially teaching others a new skill, or inspiring a new idea.

This variety of contributors and ‘leveling out’ of the population can also be seen to be having a detrimental effect on creativity in some ways – with the constant exposure to what is deemed ‘popular’ by the majority, cultures become watered down and gradually the internet communities tastes and style are in danger of becoming as collaborative as their creative power is now. The whole level of semantics and subcultures present on the internet allows for a deeper level of interaction between those from entirely different ‘real’ cultures – much in the way fads and viral videos are known the world over, customs and entire cultures face the risk of becoming ‘digitised’ and merged as the use of the internet and virtual reality continues to increase.

With such common sharing, the internet can often be seen as a free for all in terms of ownership – with images shared and appreciated with no credit or indication of the creator, it is easy for another user to ‘claim’ them as their own. The influx of storing and sharing utilities such as Facebook, Imgur and Instagram, and their often questionable or disregarded copyright and ownership terms further clouds the issue – when a user uploads someone else’s image, or an image using elements of others work, there is no simple way to derive who’s work it in fact is – often the use of a watermark is the only way to protect an image’s integrity once it’s been shared online.

The concept of a gallery is challenged by these sharing websites – a Tumblr blog is open 24 hours a day, with no need to travel or pay to enter. Sharing on sites such as twitter gives an even wider, unfiltered audience, by hashtagging and geotagging work, an unfiltered audience can access the work.

The amount of ‘space’ on the internet means there is a place for everything, with forums such as Reddit allowing people with the same interest to form a group or online community taking away any boundaries to sharing and collaborating. Any niche, big or small can be allocated its own platform. People can converse, create and collaborate from opposite sides of the world as easily as from the same studio, and it is easy to access that right person with the right information, mindset or idea

Sharing works, ideas and progress with a group can expand others’ knowledge by swapping techniques and ideas – with input, advice and criticism from the group, there is a constantly evolving and improving level of creation. People will often share their work with the understanding, and often hoping, that others will use it to directly or indirectly further their own work, and open source programs often have a large following with the belief that sharing is the best way to learn, and encourage creativity. As a result, many codes and programs will be re-used, adapted, improved and re-shared, culminating in a large number of ‘authors’ behind a piece of work. This can beg the question – When much of the work is done by a computer or influenced by random factors, and much of the input is a result of collaborative idea sharing and learning – who/what is the artist? And is this relevant to the value of the work?

THE DIGITAL, INTERACTIVE FUTURE CITY

The merger of the real and the virtual highlights the need to create adaptable future proof space, and questions how much of our lives will actually be reliant on the internet in the future. The invisible reach of the internet means we are not confined to a screen plugged into a wall and connected via dial up anymore. We are now surrounded by devices offering cloud computing, wifi – accessible anywhere, constantly connected to the internet with a constant ability to share and a constant urge to consume.

In some ways rather than the physical world finding ways to integrate technology, the virtual world is instead finding ways to integrate the real world as an extra multimedia ‘layer’ – for example location based apps and geotags are more geared towards creating a replica of a physical space in a virtual world, as opposed to creating a virtual element in the physical world. From the emergence of google street view and live webcams, people have been able to experience a level of their environment without needing to physically travel there to interact, becoming almost as accustomed to seeing the world through a screen as without.

The use of #hashtags and the instagram community create a virtual identity for a real place which creates recognition and a sense of belonging insider knowledge for locals– an online community they can relate to and feel part of..

Apps such as city geography encourage users to explore and see city in new ways

Sharing info and pictures related to the city environment causes more pride and appreciation for environment – the popularity contest of instagram means people want to create and share the best aspects of their lives. Regardless of the influences art has on their lives in a day to day instance,– recognition from social sharing makes them see and compose their life in a more aesthetic way, and further, to appreciate and see the city in a new light.

One example of this in my home city is artist Laurence Epps’s work as part of the Future Everything Festival, Manchester. In May 2013, 8000 small clay figures (echoing the figures found in Salfordian artist L.S Lowry’s paintings) were placed in busy commuter areas in the city, and passers-by were encouraged to take them and give them a new lease of life. By doing this the artist relinquished a lot of the control of the final destination for these figures and encouraged the public to stop and think, to use creativity to compose their own environment for their clay figure and share this image online.

Many of the images have been collected and presented on the website of the Sykey Art Collective. The vast amount of ideas, with both humorous and aesthetically attractive images shows the value of collaboration and interactivity – each commuter has taken their own view and interpretation of the figures and shared it in their own way, encouraging an element of creativity and fun to a large group of people who may not actively take part in creative pursuits.

It also takes the art into a more accessible form – by not presenting it in a gallery it is accessible to everyone, many of whom will stumble upon it accidentally, as well as removing a lot of the high value ‘do-not-touch’ stigma often associated with art pieces – this piece encouraged people to take, interact and play with the pieces, resulting in a wealth of images and ideas being created.

It encouraged commuters to slow down and notice the little things around them, adding an element of change, surprise and creativity to an otherwise uneventful activity which is often undertaken in an automated way, paying little attention to the surrounding environment or even other people.

Installations that can change and adapt with the city environment in relation to adhocracy and the changing needs of the environment are the best way to integrate art into the environment – the internet is causing the world to change at faster and faster speeds, and people are needing to interact with the city in different ways, with an infrastructure already in place that may not be relevant in the future, additions like this will keep the city fresh and current.

This new future is reminiscent of the virtual realities found in science fiction movies, and futuristic predictions, often cited as unrealistic and outlandish – but the fast development of technology means that the new developments are happening at a faster and faster rate – what can be learnt today is able to be put into practice immediately – allowing our knowledge to expand with fewer and fewer limits – by having the technology to try out new theories and ideas, we can instantly judge how successful they are, and see and experiment how they can be tweaked and modified to improve or change the function.